It is more than ten years ago since we completed the “Food for Thought” scenario-thinking exercise in the Nile Basin. But the outcome is still surprisingly relevant and to the point. It demonstrates the power of a well-designed and well-facilitated scenario-thinking process to better understand the contextual environment of a complex problem—and see the bigger picture. This is specifically relevant in the water sector.

Water is related to almost everything. It is essential to life, sustains critical environmental value, is at the basis of food security, is vital to numerous economic sectors, and holds important cultural and esthetic value. Understanding the complex interlinkages between water and all its functions is challenging indeed.

IWRM has given it a try. The concept is well established and useful. Nevertheless, IWRM in practice is unable to capture the full complexity of water and its role in this world. This is not always necessary, and many narrow-scope water resources problems can be adequately addressed with an IWRM approach. But at other times—specifically for complex water allocation challenges—the approach is too limited.

“Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) is a process which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources in order to maximize economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems and the environment.” (IWRM definition by GWP)

External factors that have huge influence on demand for water—and hence on water resources management—include food prices, land tenure arrangements, rural development policies, agricultural trade rules, infrastructure for bulk transport of food commodities, demographic trends, political stability, quality of governance, rural electrification, etc. We can go on.

How to include these wide-ranging factors in a meaningful and practical way in a water resources management process?

For these overly complex external environments, scenario-thinking has proven an effective tool to investigate, discover, consider, and include the bigger picture. Or put differently: scenario-thinking provides a framework to include all factors that really matter for a complex water resources management challenge—also those that are nominally outside the water sector.

Scenario Thinking

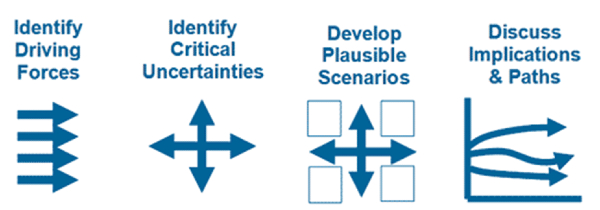

Scenarios are the primary tool of scenario-thinking—as one would expect. But it is not the scenarios that matter. Rather, it is the process that builds these scenarios, and how they are subsequently used. This requires some elaboration.

Scenarios are internally consistent stories of alternative plausible futures. They explicitly acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of the future.

Scenarios are developed in a systematic and highly participatory process. The methodology is robust and proven and involves a rigorous analysis of the driving forces that affect the issue under investigation. The scenario development process builds on the perspectives of a broad group of actors and actively discourages compartmentalization—considering only some aspects of the context rather than the full system. This process emphasizes a key objective of scenario thinking: to consider the functioning of the system as a whole—the bigger picture.

After the scenario development process is internalized, the scenarios are used in formal and informal workshop settings to explore a wide range of policy questions. Group size ranges from 2 to 20 or more. Events can be ad-hoc or facilitated. In this setup, the scenario set serves as backdrop to analyze options (for instance, to find those that are robust in all scenarios), risks, things to do, things not to do, impacts, reactions of stakeholders, areas of influence, ways to influence the course of events, etc. It is a powerful joint-thinking exercise that quickly teases out where interventions are needed, are possible, and how to sequence and time them.

A well-designed scenario thinking project is, in fact, a rapid learning exercise. It forces the group to think outside group assumptions and provides an effective framework to better understand the complex contextual environment—in a relatively short period of time. And a better understanding of the context, obviously, is a prerequisite for better decisions.

“what gives us power as humans is not our minds, but our ability to share our minds” (W. Brian Arthur)

Application of Scenario Thinking in the Water Sector

Applications in the water sector are many. For instance, preparing for a multi-year drought, the implications of urbanization on water resources management, or how to deal with a spike in global food prices. For now, however, this blog post will discuss just a single example: supporting an intractable ‘wicked’ water negotiation.

Scenario-thinking has proven a useful tool for enlarging “common ground” in complex water negotiations. The systematic and interactive scenario building process typically broadens the scope of the analysis—by reviewing and including all factors that matter, also outside the water sector—and therefore enlarges the solution space among parties. After all, a wider scope almost automatically leads to more options for ‘give and take’, and thus for a meaningful compromise. Furthermore, the group process encourages participants—often from different parties having different outlooks and interests—to share views, ideas, and ‘mental maps’. It encourages a convergence of views and joint-reframing of the problem situation, while actively building relationships.

Adam Kahane summarizes how scenario-thinking supports ‘wicked social problems’:

- transformative scenario-thinking helps us to see the bigger picture; we cannot be effective in changing what is happening if we only see our little part

- it provides a framework to think and talk with strangers and opponents, nor just friends and colleagues; in this way the actors learn to work across differences in perspectives and interests

- it helps us not to be blindsided by futures we do not want, and which we effectively ignore

- an interactive scenario project builds diverse alliances of actors; most problems are too complex to be solved by any one person or organization; the scenario project provides a practical way for diverse actors to begin working together.

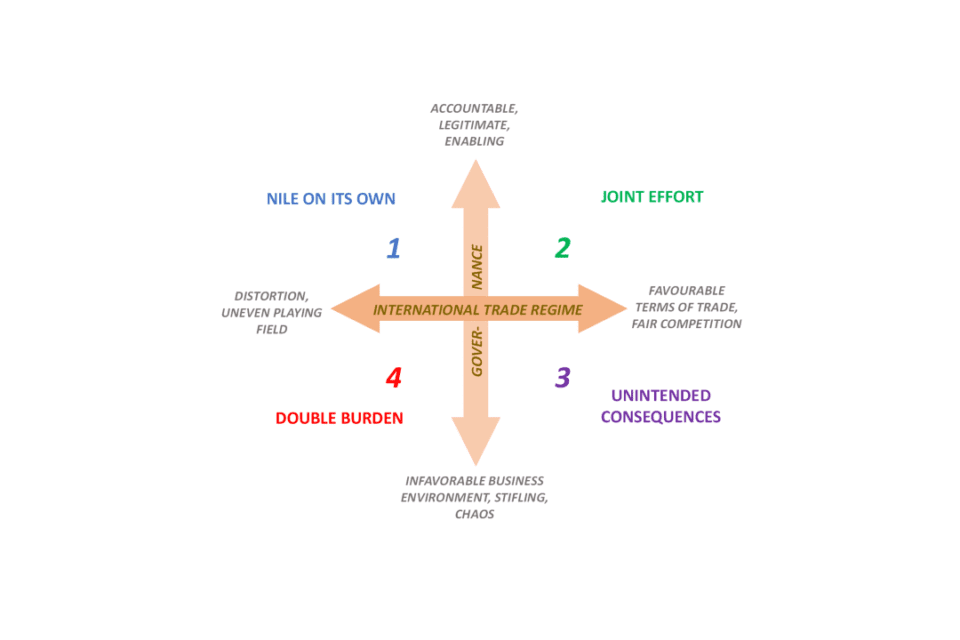

| The “Food for Thought” Scenario-Thinking Exercise “Food for Thought” (F4T) was a multi-stakeholder scenario-thinking exercise implemented by FAO in the Nile Basin. A group of some 25 decision makers, stakeholders, and experts from all Nile countries engaged in a joint scenario-thinking exercise to examine the uncertain future of the dominant driver of water use in the basin: demand for agricultural produce. The horizon year was 2030. The anticipated outcome of the exercise was to obtain a realistic range of future agricultural demand levels in the basin, as a function of population growth, urban-rural population distribution, nutrition patterns, potential of commercial agriculture focused on export, biofuels prospects, etc. The outcome would serve as input into an analysis of the agricultural water variable in the Nile basin. However, early in the process it became apparent that the structure of the demand function was determined by a much wider range of parameters than originally foreseen. The exercise had to broaden its scope. Through a highly participatory process, it evolved into a systematic analysis of the complex rural development challenge in the Nile basin—which is, in effect, at the core of the ongoing negotiations regarding Nile water allocation. It resulted in four plausible scenarios that were agreed upon by all Nile countries and that were used extensively in multiple national and international follow-up events to examine relevant policy questions related to water resources development and food security in the Nile Basin. Because of this wider perspective, the overall results of the exercise carried far more significance. Apart from answering a technical question “What will be the future demand for agricultural produce?”, the exercise resulted in significant process gains. The process of collective sense making at the regional level increased mutual understanding among participants, while new shared interests and contours of common ground were identified. |

The results of the “Food for Thought” exercise have been reported upon in an article in Reflections, which is the magazine of the Society for Organizational Learning (SOL).

Afterthought: we did not anticipate the process gains of the F4T exercise—because we were, at first, focused on a technical question. The original scenario team, therefore, included too many technical experts and not enough people with ‘a network of influence’. It taught us an important lesson for a transformative scenario exercise: always find the right balance between technical expertise and influence.