Most of us agree that we must strengthen the resilience of water systems. But where to begin? Probably best to start by examining: “what makes a system vulnerable?”.

An interesting case is irrigated agriculture along the Shabelle in Somalia.

The most striking aspect of this system is that yields are so low. Sometimes as low as 1 – 1.5 tons per hectare for maize. This is astonishingly low for a system with full water control and fertile soils. What is happening?

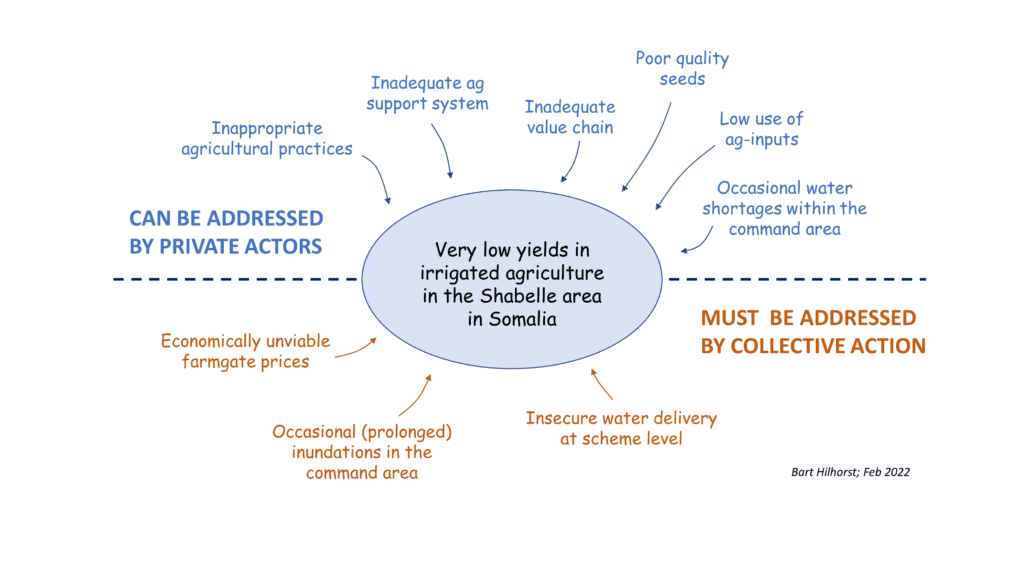

Part of the explanation is provided by the ‘usual suspects’: low use of ag-inputs, poor quality seeds, inappropriate agricultural practices, high post-harvest losses, canal sedimentation, occasional water shortages within the command area, etc. But the Shabelle story is bigger. Among the reasons for underperforming irrigated agriculture in this area is that individual farmers—or even communities—are simply unable to tackle three principal constraining factors: 1) recurrent (prolonged) inundations within the command area, 2) insecure water delivery at scheme level, and 3) economically unviable farm-gate prices.

While the first set of constrains can be addressed by private sector actors or by individual farmers (or communities), this is not the case for the last three factors. These must be addressed through collective action at a higher level, probably by some government agency.

The last three factors share another feature. Change is these factors is not caused by self-organizing feedback mechanisms. Rather, change can only be accomplished through a set of deliberate external interventions. The new arrangement (caused by these interventions), therefore, is not stable and requires constant maintenance. I think this warrants a further explanation.

Resilience 101

According to Wang and Blackmore (2014), “the essential aspect of a resilient system is that it has an adequate capability to avert adverse consequences under disturbances, and a capacity of self-organization and adaptation, and thus displays a greater capacity to provide wanted services that support our, and the environment’s, quality of life”.

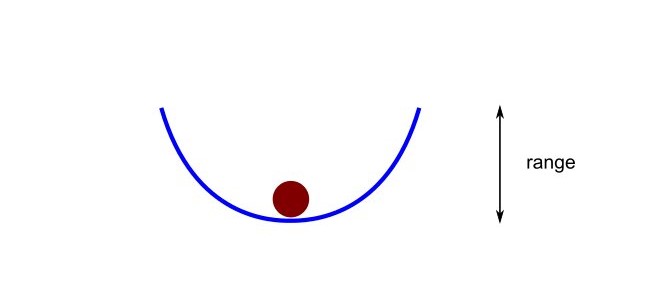

Resilience in a stable system is maintained by self-organizing feedback mechanisms. This is illustrated by the ‘ball-and-cup’ analogy in the below figure. A disturbance may move the ball, but it will quickly return to a stable position at the lowest point of the cup.

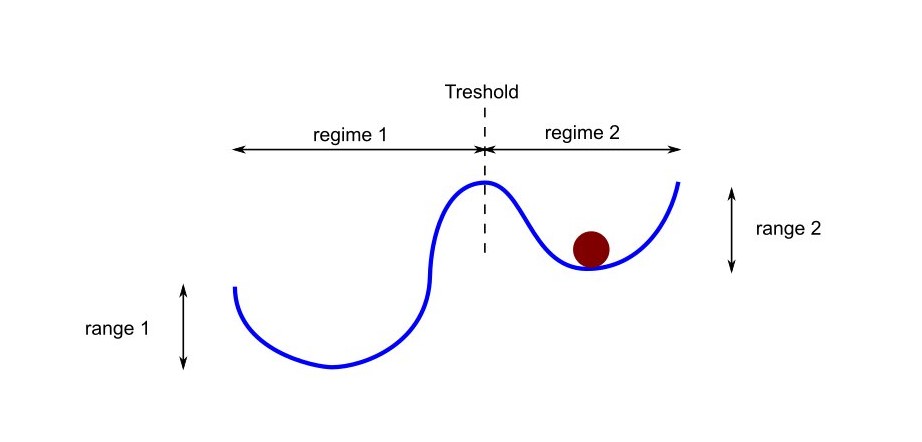

A regime shift will only happen when a critical threshold is crossed (see below figure). Regime shifts are sudden and difficult to reverse. After the sudden transformation, the new regime is substantially different from the previous one. Note that for a resilient system, the new regime is once again maintained by stable feedback mechanisms.

Flood protection in the Shabelle: a more productive but vulnerable regime

With the above in mind, what can we say about the resilience of an (imaginary) irrigation system in the Shabelle that is protected from floods?

Bank-spill along the Shabelle can leave fields inundated for a prolonged period because of the inverse topography of the alluvial zone, in which the river is higher than the surrounding land. It means that floodwater that have spilled over the embankment cannot return to the river—even when river levels recede. Instead, this water accumulates in low-lying areas within the irrigation scheme and can remain there for months until all water has either evaporated or percolated. It has severe negative impacts on crop yields and agricultural production and is among the principal reasons for the exceptionally low yields.

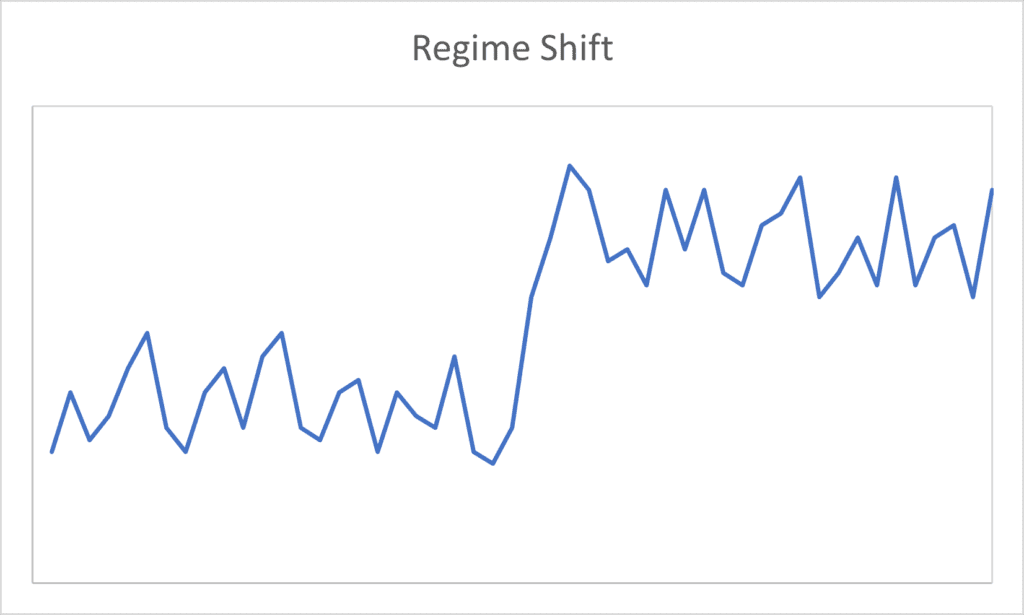

Thus, dealing with floods will likely initiate a regime shift in irrigated agriculture. Average yields will probably experience a significant jump (see figure below). This new and more favorable regime, however, is caused by an external intervention—adequate flood protection—and not by some stabilizing feedback. Thus, this new system is not stable and will require constant maintenance. Else it will inevitably revert to the old state that was characterized by frequent inundations and low yields. Irrigated agriculture along the Shabelle in Somalia, therefore, is inherently vulnerable and depends on continuous external interventions.

More productive irrigated agriculture along the Shabelle is inherently vulnerable

A similar analysis can be made for the other two critical constraining factors in irrigated agriculture in the Shabelle basin: low farmgate prices and insecure water delivery at scheme level. Both cannot be addressed by individuals. It will require an external intervention—at some government level—to create an environment in which yields can go up, probably quite substantially. But, once again, this new arrangement remains vulnerable. It can only be maintained by deliberate and sustained action at an appropriate government level, lest the system will eventually but inevitably move back to the old state characterized by much lower productivity.

Note that the set of actions that individual farmers can take on their own—such as adopting improved seeds or use of ag-inputs—are much less effective if agriculture remains vulnerable to floods or systematic water shortages at scheme level.

What are the implications of the above analysis?

Let’s start with three observations. They are concerned with 1) the role of government, 2) the quality of infrastructure, and 3) sequencing of interventions; they will be discussed briefly in the remainder of this post.

The role of government

I think irrigated agriculture in the Shabelle basin in Somalia provides a case study of what happens when government is almost completely absent for 30 years or so. In short, it leads to astonishingly and stubbornly low yields, despite good soils and quite a lot of water. It seems inevitable that some sort of super-structure is needed to create an environment in which individual farmers ‘can solve their problems’. The exact setup of this governance structure is not something that can be decided by outsiders, but it needs to take care of issues that are too big for individuals to handle, such as flood protection and equitable water allocation among schemes.

Fortunately, the mantra that ‘government is the problem’ is in retreat. It has done damage.

Built-to-last

When you are not sure that budget for maintenance is available—year in, year out—common sense would dictate that infrastructure is best ‘built to last’. Perhaps even more so for infrastructure that is essential to provide the conditions for significantly higher productivity.

A previous blog post discussed the limitations of the Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA). I remain suspicious of this tool. A CBA may be useful for fast-moving business ventures, but perhaps not for critical infrastructure on which many people rely for their livelihood and safety.

Hence flood protection along the Shabelle, I would argue, should look for long-lasting solutions that require as little maintenance as possible. This implies large geo-textile tubes (or similar solutions) rather than narrow dikes, sandbags, or other band-aid measures. Yes, it will be more expensive, but also more durable and much less vulnerable and most importantly will keep irrigated agriculture in a more productive state. In addition, flood protection measures would preferably include redundancies (such as a parallel dike that may be lower and smaller but serves as a back-up) or create a series of independent modules that would remain dry if flood defenses are breached in another module. These types of measures have been applied across the globe. I think it’s mostly common sense.

Sequencing of interventions

Final thought: sequencing of interventions matter. There is little value in securing higher farmgate prices when irrigated agriculture is still vulnerable to periodic inundations that can last for months. For the Shabelle, is seems flood defenses are the priority, followed by secure water supply at scheme level. Only when these two matters are successfully addressed would it make sense to focus on other constraining factors. I would say higher farmgate prices are next in line. Measures to address the remaining constrains will hopefully follow—in an autonomous process initiated and implemented by individual actors—when a proper enabling environment is in place.

The following observations were made by my colleague Peter Muthigani:

- Low food prices are partly caused by WFP distributed food that is taken to local markets and competes with locally produced food. This is because there is usually a time-lag between a calamity—which is the reason for a food deficit—and the response by WFP and other agencies. Hence food aid is on occasion only delivered during the next harvest.

- Emergency repairs of embankments are also affected by operating procedures of international donor agencies. On occasion, embankments cannot be repaired before the next flood season because of delays in disbursement of funds for procedural reasons. It underscores the importance to ‘built-to-last’.

REFERENCES

Assessment of human–natural system characteristics influencing global freshwater supply vulnerability, Julie C Padowski et al 2015 Environ. Res. Lett. 10 104014

Resilience Concepts for Water Resource Systems; Wang C., and Blackmore J.; Journal of Water Resources Planning and Management · November 2009

Stockholm Resilience Centre: diverse videos