For a long time now, the river basin has been the central unit for water resources management. There were—and still are—good reasons for this. A practical argument is that it makes it easy to quantify the available water resources. A closely related argument is that water allocation mechanisms need to consider the entire (groundwater) basin to be effective. Yet another rationale is that it acknowledges the close relation between water and land management—and by association agricultural practices—and that many measures that promote responsible land stewardship, with beneficial impacts on the hydrological cycle, are best implemented for the entire catchment to make a meaningful impact.

A fourth reason is that it reflects the geographic jurisdiction of the basin manager. Issuing permits and promoting and/or managing water infrastructure are probably a basin managers’ most effective tools to regulate water use, optimize the societal benefits of scarce water resources, protect important environmental value, and ensure that conflicting water uses are avoided or managed. Obviously, he or she can only issue permits or establish water works, or initiate other interventions, within his/her own basin. I know this is a circular argument but, nonetheless, it cements the prime focus on the river basin.

Nevertheless, the watershed focus also introduces a bias. It blurs—almost surreptitiously—the important role of many non-biophysical factors on water-use, demand, and protection. It also limits the solution space when trying to address the myriad water challenges.

This post will discuss why—and at which scale—the watershed bias is something to worry about.

| Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) IWRM is a cross-sectoral policy approach designed to replace the traditional, fragmented sectoral approach to water resources management that has led to poor services and unsustainable resource use. Integrated Water Resources Management is based on the understanding that water resources are an integral component of the ecosystem, a natural resource, and a social and economic good (UNEP). |

The Bigger Picture

The IWRM approach aims to (consciously & practically) acknowledge that water is integrated in many aspects of the environment and the economy and that water resources, therefore, must be managed in a holistic manner that considers all these various uses, purposes, and factors.

There is nothing wrong with this approach. But, if water is related to almost everything—and conversely, ‘almost everything is related to water’—where do you draw the line?

Let’s concretize this discussion with an example.

Water scarcity in a river basin is typically caused by high demand for irrigation water. Reason is that agricultural/food production—in a water-scarce basin—is almost inevitably the dominant water user. After all, it takes lots of water to grow a crop or support livestock—thumb rules are 1000 liters of water for 1 kg of wheat, and 10,000 liters for 1 kg of meat (these figures are indicative; the exact numbers vary per climate zone and farming system; but you get the point). Note that demand for basic food items is not elastic because a minimum calorie intake is required for a healthy and productive life. Low-income consumers without access to subsidized food—which includes a large share of the rural population in developing countries—require locally produced cheap food. This requires a lot of water that cannot be subjected to market forces as it would deprive rural people of their livelihood and jeopardize their food security.

Water demand for other sectors is (far) less critical. Industrial water use normally responds to price signals, while water for domestic purposes is just a fraction of what is used for food production. Thus, water demand (and security) for agricultural production is what matters in a typical water scarce basin. It follows that the principal task of a water agency confronted with this situation is clear: supply adequate volumes of irrigation water in a timely manner.

Or so they say…

Because it’s not all about water; there are other factors involved in food security. First: some 30% (or more) of food produce is lost in the chain from harvest to household. Another significant percentage is lost within the household. Reducing food waste would directly and proportionally reduce demand for water (and thus ease the basin manager’s task to address conflicting water demands…). Second: food can be imported from outside the basin. Third: water is not the only constraint in the agricultural production system; interventions in other areas such as the provision of ag-inputs or improved seeds have a major impact on water productivity in the agricultural sector. Fourth: viable farm-gate prices—and associated price stability—for agricultural produce greatly influence farming processes and, consequently, water productivity. We can go on.

The point I wish to make in the above example is that water scarcity can also be addressed by actors and measures that are nominally outside the water sector. In fact, interventions from outside the water sector— such as reducing food waste or guaranteeing viable farmgate prices—are occasionally much more effective in the overall attempt to balance water supply and demand.

Note that many of these interventions—to improve agricultural production and thus make more efficient use of water—require policy interventions at nation state level.

There are many other examples of the need to see the ‘bigger picture’ when managing water resources.

So, what is the role of the basin manager in all this?

| The Blind Men and the Elephant The above example is illustrated by the parable “The Blind Men and the Elephant”, which exemplifies the importance of the complete context. The parable is also a warning not to fall for the reductionist fallacy: the idea that complex phenomena can be better explained by “reducing” them into small, simple pieces. |  |

An Activist Role?

The example presented above suggests that while a basin manager has (some) influence in the geographic area defined by the watershed, his/her focus must be broader.

After all, only when all constraining factors in a complex process are addressed—also those outside the jurisdiction of the basin manager—will it (in most cases) be possible to find a balanced and effective solution. In fact, by looking at the full spectrum of constraining factors, including non-biophysical ones, the ‘solution space’ for a wicked water resources challenge is typically enlarged. This would automatically increase the potential to find a solution that satisfies all (or at least more) stakeholders.

By contrast, if the water manager only addresses those factors about which (s)he has some control, the ensuing solution will inevitably be sub-optimal and most probably contentious. Because stakeholder will know—if only intuitively—that ‘this is not a good and fair solution’.

The question now is whether the basin manager is the appropriate person to take on this ‘activist role’.

In my experience, basin managers are overwhelmed by manifold issues—small, large, critical, vital, urgent, super urgent—which fully commits their time and attention. Accepting yet another responsibility as ‘activist/lobbyist’ at national level will not be realistic for most. And even if they would enjoy taking on this additional role, they will probably not be able to give it the attention that it deserves and requires.

A Complementary Task

The above discussion implies that the primary focus on the basin as the central unit for water resources management is practical and justified for many good reasons—but not enough.

The water management architecture—now dominated by this basin structure in many countries—needs to be complemented with an entity that looks at the bigger picture. It should identify ‘non-water factors’ that have a major impact on water use and water demand—and water security in general—such as agricultural policies, land tenure arrangements, food waste, agricultural trade arrangements, power pooling, or land use policies in the floodplain, to mention just a few.

The task of this entity is then to coordinate with the relevant line ministry (and other agencies) to harmonize these factors and ensure that they foster effective and sustainable water management. It is a coordination and lobbying role that tries to influence laws and regulations outside the immediate water domain. Nevertheless, it is a very important role since these ‘non-water factors’—which are outside the jurisdiction of water managers at basin and national level—can have a major impact on achieving overall water security at multiple levels, as discussed above.

In this regard, this dedicated entity should be powerful, high-up in the ministerial hierarchy, and staffed with ‘big hitters’ with a network of influence and the capacity to influence relevant policies and regulations of other ministries. Note that a weak entity—that just exists on paper and is unable to influence relevant policies—would serve no purpose whatsoever.

Closing Remarks

This post has argued that it is important to see the complete context—including elements outside the water sector—to increase the effectiveness of water resources management and find negotiated solutions for wicked water issues. A basin focus alone inevitably introduces a basin bias and represents a variation of the reductionist fallacy. It reduces the negotiation and solution space and leads to sub-optimal solutions and use of scarce water resources. Hence a dedicated effort is needed to enlarge the perspective. How this is achieved will vary per organization and country. It will not be easy because this activist/lobbying role is fuzzy and will require lots of stamina. Nevertheless, I think this effort is crucial to manage water resources effectively and sustainably for the benefits of all stakeholders in the basin and country.

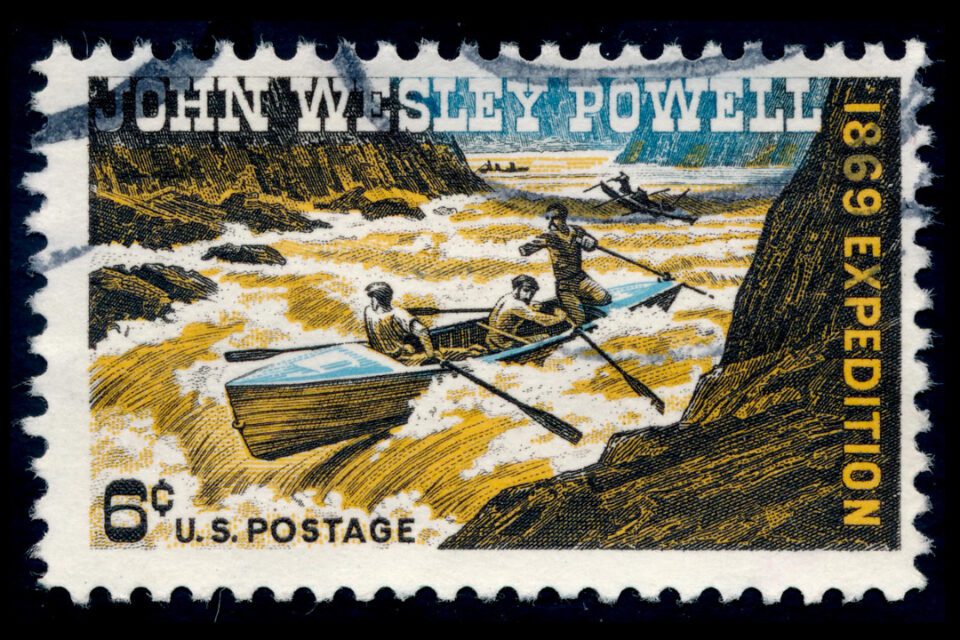

John Wesley Powell

John Wesley Powell had figured out long ago that there are benefits if political boundaries in a water scarce region are based on natural divisions of landscapes, such as the watershed. It is beautifully explained—as always—in the below video by Andrew Millison. Powell’s ideas resonate but are, of course, not practical given the existing well-established administrative boundaries. Hence the compromise suggested in this blog post.