A paradox is a seemingly contradictory proposition that yet is perhaps true. Below I have listed several contemporary paradoxes in water resources management that you probably encounter on a regular basis.

- Water is vital to life, environmental value, and socio-economic development, but society is generally not willing to make adequate funds available for its protection and management.

- Many large-scale water allocation conflicts are best addressed with solutions found outside the water sector; these solutions are nevertheless rarely considered because they are outside the jurisdiction of water managers.

- Silo thinking is prevalent in Integrated Water Resources Management.

- Holistic management of natural resources was common in traditional societies (with limited resources and limited understanding of complex natural systems) while modern society (with tremendous scientific knowledge and resources) fails to manage natural resources in an integrated manner.

- In many places, government is mistrusted but effective water resources management cannot happen without collective action and management facilitated by government.

- Optimizing water use is the wrong approach for most river basins where water is scarce.

- Substantial parts of most large-scale public irrigation schemes are water insecure (note that irrigation was introduced to provide water security).

We can go on.

Each of the above paradoxes is associated with longstanding and intractable problems in water resources management and huge efforts—mostly paid for with public funds—have been made in the last decades to address these issues. Usually without much avail. The lack of apparent success is problematic. In the first place, of course, because critical water resources issues have been left unaddressed but also because of the (legitimate) concerns about the effectiveness of these interventions. Water resources management—at scale—is almost entirely dependent on public funding. There is huge competition for government money. It will be difficult to continue asking for additional public funds after previous efforts have not delivered the expected results.

Given this context—and the unprecedented pressure on water resources—it makes sense to take time to carefully think about these paradoxes (plus, of course, all similar ones not listed above).

Paradoxes often emerge when a sub-system is being confused with the total (overarching) system. For those of us remembering MS DOS, it is similar to mistake “*.sub system” for “*.*”. Many attributes of a sub-directory are not valid for the main directory, and vice versa.

Thinking that a sub-system represents the entire system and is therefore ‘’stand-alone” and bounded—thus, not impacted by outside systems, and not impacting on outside systems—is a common and convenient error because:

- It is intrinsically not possible to fully understand a complex natural system and its myriad inter-sectoral interactions. This is referred to as ‘bounded rationality’—when perfect knowledge of (all) possible future events and all their consequences is simply unattainable.

- Humans are hardwired to ignore complexity webs; rather, we (homo sapiens) naturally gravitate towards a reductionist approach as mental ability is a limited (and scattered) resource; it impedes quick comprehension of highly complex systems.

- Individual rationality encourages actors to ignore negative consequences outside their own subsystem; it highlights the tension between individual and collective interest; in some cases, it represents the tragedy of the commons; in others it can be regarded as a ‘collective prisoners dilemma’.

“We are a creature of economy” Dr. George Simon

By itself, each of the above three factors is a strong driver to ignore the big picture and focus only on a specific subsystem and disregard collective interests. The facile response “it is not my problem” is all too common when adverse consequences of decisions taken in a sub-system spill-over to other parts of the system. Unfortunately, this works both ways.

Given the strong forces that push towards reductionist thinking, it constitutes the dominant strategy in the water sector and there is consequently an inherent bias against integrated solutions and (large-scale) cooperation—despite IWRM’s good intentions.

If we presume that integrated (long-term) solutions remain critical to sustainable and equitable water resources management, we somehow need to overcome this reductionist bias. How to do this?

The remainder of this post will suggest 3 strategies to counteract the reductionist bias: scenario thinking, causal diagrams, and regulations. Other mechanisms—not discussed in this post—include establishing a web of (small) no-regret solutions (and just see what integrated solutions emerge) and reducing complexity by knowing what not to do.

Scenario thinking

Scenarios are internally consistent stories of alternative plausible futures. They explicitly acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of the future. However, it is not the scenarios—per se—that matter. Rather, it is the process that builds these scenarios, and how they are subsequently used.

Scenarios are developed in a systematic and highly participatory process. The methodology is robust and proven and involves a rigorous analysis of the driving forces that affect the issue under investigation. The scenario development process builds on the perspectives of a broad group of actors and actively discourages compartmentalization—considering only some aspects of the context rather than the full system. This process emphasizes a key objective of scenario thinking: to consider the functioning of the system as a whole—the bigger picture.

Compartmentalized thinking can be equated with ‘living in a room without a window’. There is no way to see how you are connected to the outside world; you cannot develop a perspective. A scenario exercise will equip the room with a panorama-size window that allows you to discover the bigger picture.

Scenario thinking has been covered in a previous post.

Causal diagrams

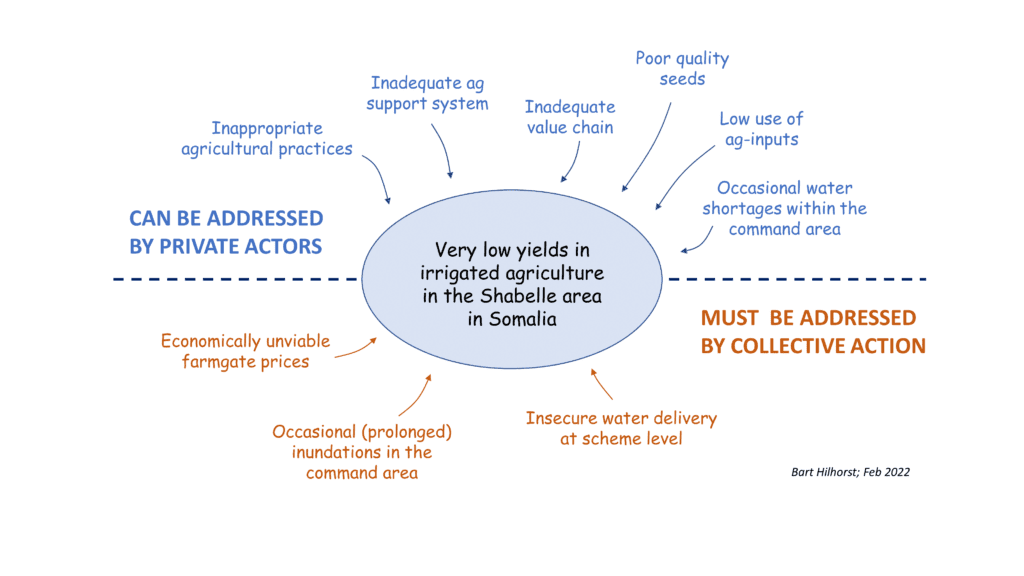

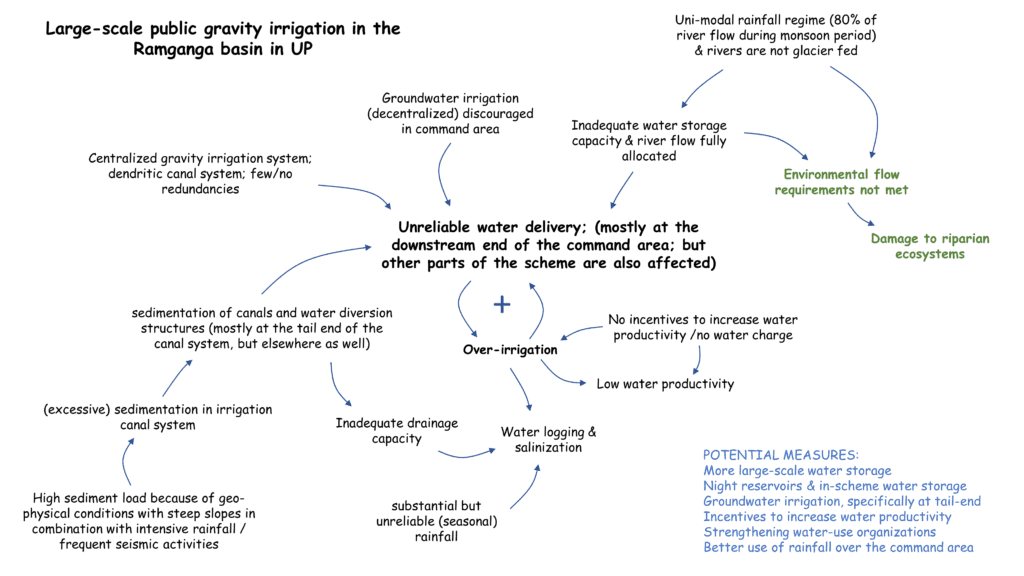

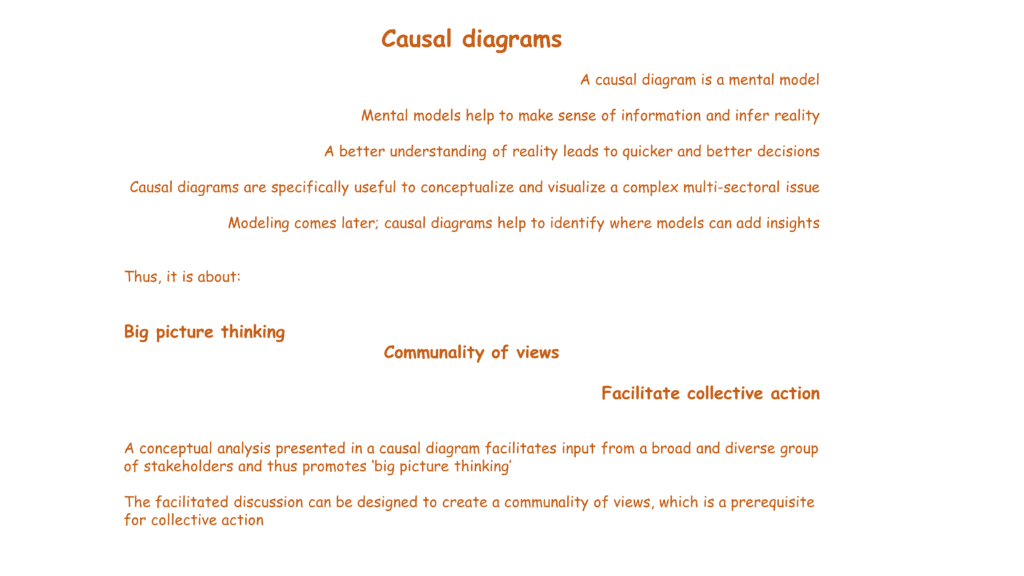

Once you see the bigger picture, a set of causal diagrams can help you to understand it. A causal diagram is a conceptual analysis presented as a graph. It is specifically useful to visualize a complex multi-sectoral problem.

“Everyone hears only what he understands” Wolfgang von Goethe

A causal diagram simplifies reality, ignores a lot of information, does not require computations, and does not provide probabilities. Nevertheless, it provides a framework that allows for a structured and participatory analysis by a diverse group of stakeholders. More detailed analysis—which can include modeling—come later in the decision-making process. Note that the bigger picture is often lost once you engage in more detailed analysis.

Regulation

Regulations are useful when actors ignore the bigger picture even though they are aware of it. Hence regulations, in this context, serve to protect collective interests.

The Water Framework Directive of the European Union is an excellent example. It commits EU member states to achieve good qualitative and quantitative status of all water bodies and prescribes steps to reach this common goal. Since it is a legal obligation, nobody gets away with, for instance, polluting the environment (and thus avoid costs and have a comparative business advantage) while all others have undertaken to establish treatment facilities. Regulations serve to avoid the ‘tragedy of the commons’. It is recognized that developing sensible regulations that are widely accepted is a time-consuming and difficult process.

Closing comments

Solving paradoxes generally requires a broader perspective. This is contrary to pervasive reductionist thinking in water resources management. Only considering a sub system, however, is a time bomb. The more pressure on scarce water resources, the faster the clock ticks. Deliberate action, therefore, must be taken to resist reductionist thinking. It will require time and communication.

Scenario thinking aims to see the bigger picture, causal diagrams help to understand it, and regulations serve to protect higher level interests that would otherwise be ignored. All three instruments are part of the toolbox to foster IWRM and consider the entire system. They thus contribute to solving contemporary paradoxes in water resources management.

References

Rustpunten van de Geest, Filosofie van Gezondheid, Waarden, en Zingeving; Arnold Cornelis, 1999 (in Dutch)