The contextual environment

A previous post on this blog sketched the contextual environment in which water resources are managed. To summarize:

- Most protracted water resources issues are highly complex and not fully understood, and there is no clear course of action to address these wicked WRM issues.

- Water resources management capacity to deal with protracted WRM issues is inadequate across the board; this is unlikely to change because of budgetary constraints at all relevant government levels; note that complex issues exceed the capacity of local communities or institutions and do require government involvement at some stage.

- The institutional setup of WRM and the political nature of the water allocation process fosters compartmentalized decision making and sub-optimal resource allocation.

- Mental resources are scarce, and humans are hard-wired to ignore the ‘web of complexity’ in societal, environmental, or economic systems.

- Establishing the requisite infrastructure (hard and soft) for effective water resources management is often a multi-generational undertaking.

The above context creates strong drivers for water managers to ignore the ‘big picture’ and instead follow a reductionist approach. This typically leads to a plethora of scattered and uncoordinated WRM interventions that ultimately prove ineffective and fail to resolve the protracted issue.

How to go about this?

The complexity fallacy

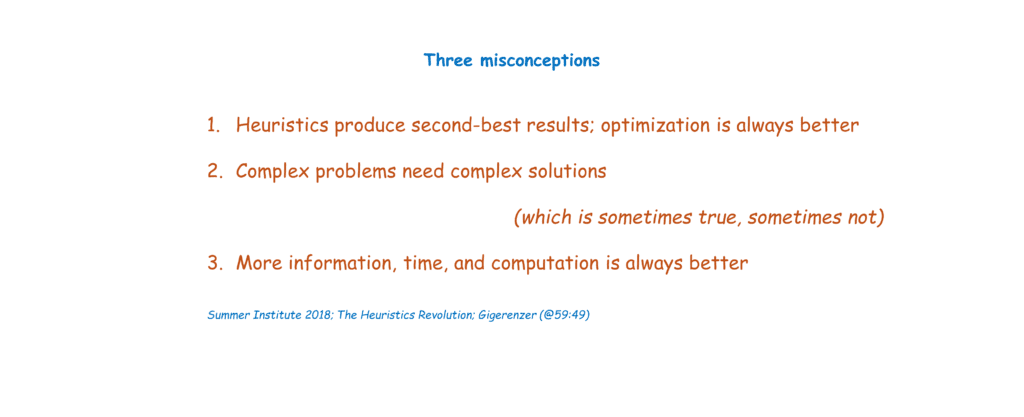

According to Gerd Gigerenzer— a German psychologist—a key attribute of human intelligence is ‘knowing what to ignore’. He asserts that humans use shortcuts for the majority of complex problems they must deal with. In practice, they typically consider just one or a few factors when taking decisions, rather than the entire range of aspects that impact on a complex problem. This observation contrasts with the widely held belief that complex problems need complex solutions. While this may be true for some cases, for others a heuristic may prove effective.

“The complexity fallacy: complex problems always need complex solutions”

What would such heuristic look like in the water resources sector? The next paragraph provides an example.

Three-point checkup for WRM interventions

When resources are limited—in terms of budget, time, managerial capacity—it is prudent to carefully select the interventions that will be pursued. After all, it would be wasteful to focus scarce resources on something that is not necessary or effective.

With the above in mind, a three-point checkup for WRM interventions was prepared. The checkup is a ‘fast & frugal’ decision tree to determine whether an intervention should be considered at all. It is an example of a simple heuristic that will (greatly) simplify decision processes in the water resources sector. The heuristic is based on the thinking of Peter Drucker.

The above heurist is illustrated in 3 examples.

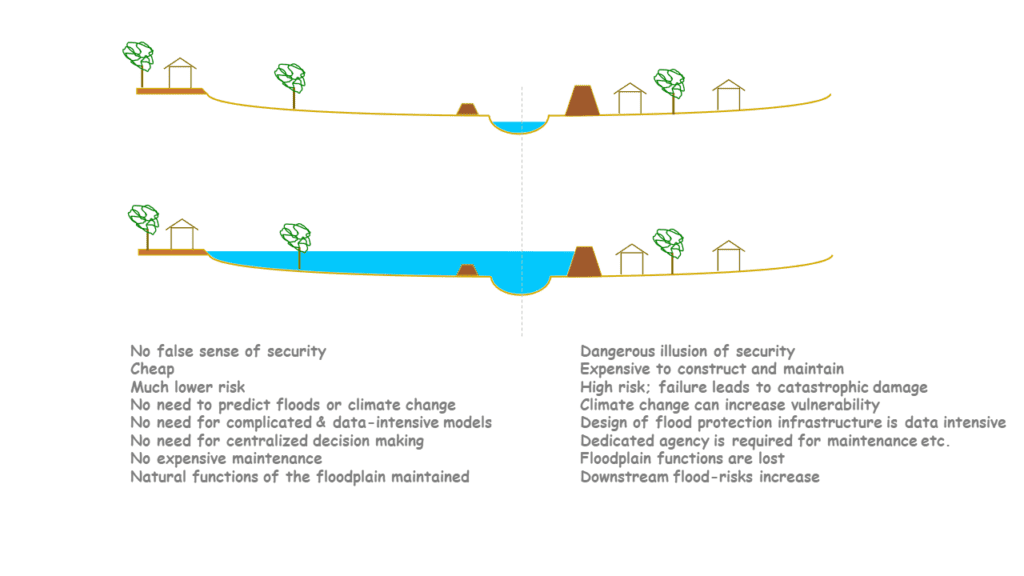

Proposed intervention 1: construct levees along a river that will provide protection from 1 in 50-year floods.

Question 1: Should this be done at all?

Discussion: Establishing levees along the entire river is a huge investment. It will, however, not prevent flooding because it is certain that a 1 in 50-year flood event will be exceeded sooner or later. The levees, therefore, provide a false sense of security. As memories of past floods fade, people will be tempted to make large investments in property and/or infrastructure in areas that remain vulnerable to flooding. Once the inevitable high flood occurs, it could lead to huge damage and possibly even loss of life. Thus, rather than providing security, the levees have created high risks and high potential damage.

This intervention should therefore be rejected. A robust policy is to either provide flood defenses that protect the floodplain from extreme flood events or accept that the area will occasionally be inundated, and then adapt to this reality. One can argue that a levee system that provides protection for 1 in 50-year events represents the worst of all worlds: false security rather than security.

Decision: reject / reconsider

Proposed intervention 2: expand a large public gravity irrigation system

Question 2: Does it support a key objective?

Discussion: Secure water supply is a precondition for agricultural modernization and huge investments have been made in large public irrigation schemes that are intended for smallholders. These systems, however, have persistently underperformed and have proven difficult and expensive to maintain. Water productivity is typically low and large parts of the irrigation system—specifically at the tail-end of the canal system—are effectively water insecure. Moreover, the remaining water off-take potential in most rivers that supply large irrigation schemes is very limited.

In this context, further expanding the command area does not make sense. Rather, possible interventions should focus on increasing water productivity in the existing scheme. The water still left in the river system is best allocated to maintaining environmental flows and water quality standards. At this point in time, maintaining environmental value is generally prioritized over a marginal increase in the command area of a scheme characterized by subpar productivity.

Decision: reject.

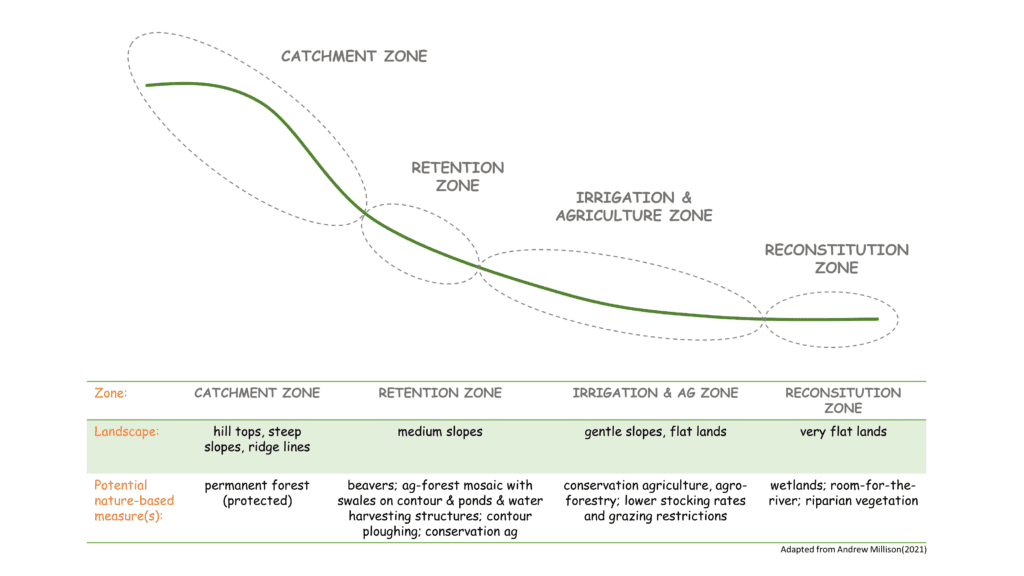

Proposed intervention 3: establish nature-based solutions—such as wetlands, reed beds, or tree planting in the riparian zone—to provide flood protection in the floodplain of a medium size river.

Question 3: Is the approach effective and sustainable?

Discussion: nature-based solutions employ natural processes to achieve water-related objectives. In essence, they are concerned with managing vegetation, soils, wetlands, and floodplains with the aim to slow-down the speed at which water flows through the landscape. Water quality is improved along the way through biological processes.

However, while nature-based solutions are promising in principle, they can be overwhelmed by the scale of the challenge. What works well in a small watershed may not work in a larger one. A case in point is flood protection in a medium size or large river. Flood volumes are huge and will probably increase because of climate change and ‘global weirding’. Thus, effective nature-based solutions to buffer or retard the flood wave must be implemented at an enormous scale. This is not a realistic proposition for most river basins and most flood challenges. Therefore, stand-alone nature-based solutions for large scale challenges are not effective in most cases. Hence, they are best combined with civil works such as levees, polders, or artificial mounts.

Decision: reconsider; implement nature-based solutions in combination with civil works.

Ecological rationality

Ecological rationality is defined as “the successful match between a strategy (e.g. a heuristic) and the structure of the environment” (Gigerenzer; The intelligence of intuition; page 97). It is based on the notion that most heuristics are not universal. Rather, they are only effective in the specific environment for which they have been designed.

So, in which specific environment is the proposed three-point checkup heuristic effective?

This environment has been described in the first paragraph of this post and is summarized as: an uncertain environment with inherent budgetary constraints and limited funds for investments in water resources infrastructure; the environment is further characterized by grossly inadequate water resources management infrastructure across the board for which there is no short-term fix, and which therefore requires a long-term multi-generational perspective.

By fostering ‘no regret’ and robust solutions, the ‘fast and frugal’ three-point checkup heuristic will avoid white elephants, fads and short-lived trends, ‘trial and error’ projects with uncertain outcomes, solutions that are financially unsustainable and lock-in long-term maintenance costs, and decisions based on short-term considerations such as a cost-benefit analysis. It is intended to focus investments on long-term key priorities and avoid wasting scarce investment funds.

Hence the three-point checkup heuristic is a useful augmentation of the water resources manager’s adaptive toolbox.

Common misconceptions regarding heuristics:

REFERENCES

The Intelligence of Intuition; Gerd Gigerenzer, Cambridge University Press, 2023